Introduction

Before we explore the forensic utility of systemd journals, we need to understand what systemd is and what systemd-journal.service is. Understanding them makes the picture a little clearer for us as we would know what we would find in there.

The manual page for systemd contains a very straight-forward and easy to understand description -

“systemd is a system and service manager for Linux operating systems. When run as first process on boot (as PID 1), it acts as init system that brings up and maintains userspace services. Separate instances are started for logged-in users to start their services.”

You can read more about it here - https://www.freedesktop.org/software/systemd/man/latest/systemd.html

Now moving to systemd-journald.service -

“systemd-journald is a system service that collects and stores logging data. It creates and maintains structured, indexed journals based on logging information that is received from a variety of sources”

The sources as per documentation include:

- Kernel log messages, via kmsg

- Simple system log messages, via the libc syslog(3) call

- Structured system log messages via the native Journal API

- Standard output and standard error of service units.

- Audit records, originating from the kernel audit subsystem

The journal service writes the journal files commonly to two locations based upon journal configuration

- /var/log/journal -> Persistent logging (Default)

- /run/log/journal -> Volatile logging. The logs are deleted at system reboot.

The configuration can be changed by changing the values in the /etc/systemd/journald.conf file.

For further reading:

- https://www.freedesktop.org/software/systemd/man/latest/systemd-journald.service.html

- https://www.freedesktop.org/software/systemd/man/latest/journald.conf.html

If you are on Linux machine using the following would give you this same information.

$ man systemd

$ man systemd-journald.service

$ man journald.conf

Default Journald Configuration

I am testing on a Ubuntu 24.04 desktop VM and the default configuration is:

$ systemd-analyze cat-config systemd/journald.conf

# /etc/systemd/journald.conf

# This file is part of systemd.

#

# systemd is free software; you can redistribute it and/or modify it under the

# terms of the GNU Lesser General Public License as published by the Free

# Software Foundation; either version 2.1 of the License, or (at your option)

# any later version.

#

# Entries in this file show the compile time defaults. Local configuration

# should be created by either modifying this file (or a copy of it placed in

# /etc/ if the original file is shipped in /usr/), or by creating "drop-ins" in

# the /etc/systemd/journald.conf.d/ directory. The latter is generally

# recommended. Defaults can be restored by simply deleting the main

# configuration file and all drop-ins located in /etc/.

#

# Use 'systemd-analyze cat-config systemd/journald.conf' to display the full config.

#

# See journald.conf(5) for details.

[Journal]

#Storage=auto

#Compress=yes

#Seal=yes

#SplitMode=uid

#SyncIntervalSec=5m

#RateLimitIntervalSec=30s

#RateLimitBurst=10000

#SystemMaxUse=

#SystemKeepFree=

#SystemMaxFileSize=

#SystemMaxFiles=100

#RuntimeMaxUse=

#RuntimeKeepFree=

#RuntimeMaxFileSize=

#RuntimeMaxFiles=100

#MaxRetentionSec=

#MaxFileSec=1month

#ForwardToSyslog=no

#ForwardToKMsg=no

#ForwardToConsole=no

#ForwardToWall=yes

#TTYPath=/dev/console

#MaxLevelStore=debug

#MaxLevelSyslog=debug

#MaxLevelKMsg=notice

#MaxLevelConsole=info

#MaxLevelWall=emerg

#LineMax=48K

#ReadKMsg=yes

#Audit=yes

# /usr/lib/systemd/journald.conf.d/syslog.conf

# Undo upstream commit 46b131574fdd7d77 for now. For details see

# http://lists.freedesktop.org/archives/systemd-devel/2014-November/025550.html

[Journal]

ForwardToSyslog=yes

A very detailed description of each of these fields is given in https://www.freedesktop.org/software/systemd/man/latest/journald.conf.html

Journal Files

By default the journals are written to /var/log/journal/

$ ll /var/log/journal/f07636b32dca4f1c8d9b580d2075a568/

-rw-r-----+ 1 root systemd-journal 8388608 May 12 23:10 'system@0006184553415ca8-0b6983cf4087b9e2.journal~'

-rw-r-----+ 1 root systemd-journal 8388608 May 12 23:15 'system@0006184567d9baef-fbdee9c5be87ccad.journal~'

-rw-r-----+ 1 root systemd-journal 8388608 May 12 23:15 'system@be528d16c6b94486b289969e1c027ec8-00000000000013f8-00061845533ee707.journal'

-rw-r-----+ 1 root systemd-journal 8388608 May 12 23:31 'system@da38f06137514d1ba21820d90ee8a479-0000000000003bea-000618458aa5bcf1.journal'

-rw-r-----+ 1 root systemd-journal 8388608 May 12 23:27 'system@f59e783aa9ca46d3ab04563cd8afd391-0000000000001f83-0006184567d740a8.journal'

-rw-r-----+ 1 root systemd-journal 8388608 May 12 23:28 'system@f5dd08973418488f8446d078178285dc-0000000000002e33-0006184581a5a812.journal'

-rw-r-----+ 1 root systemd-journal 8388608 May 12 23:30 'system@f5dd08973418488f8446d078178285dc-000000000000380e-00061845834e166b.journal'

-rw-r-----+ 1 root systemd-journal 8388608 May 12 23:32 system.journal

-rw-r-----+ 1 root systemd-journal 8388608 May 12 23:10 'user-1000@0006184555107953-0af7d4f81de2e446.journal~'

-rw-r-----+ 1 root systemd-journal 8388608 May 12 23:15 'user-1000@00061845687b086c-35bb8752a264139b.journal~'

-rw-r-----+ 1 root systemd-journal 8388608 May 12 23:15 'user-1000@be528d16c6b94486b289969e1c027ec8-0000000000001db9-0006184555107867.journal'

-rw-r-----+ 1 root systemd-journal 8388608 May 12 23:28 'user-1000@f59e783aa9ca46d3ab04563cd8afd391-0000000000002953-00061845687b06b9.journal'

-rw-r-----+ 1 root systemd-journal 8388608 May 12 23:31 'user-1000@f5dd08973418488f8446d078178285dc-000000000000380d-00061845834d5387.journal'

-rw-r-----+ 1 root systemd-journal 8388608 May 12 23:32 user-1000.journal

There is something very interesting about the naming of the files here. Let us take user-1000@f5dd08973418488f8446d078178285dc-000000000000380d-00061845834d5387.journal as example here.

- user-1000 is the User ID. You can cross-verify this by examining the contents of /etc/passwd.

- The last hexadecimal sequence in the name 00061845834d5387 is the timestamp corresponding to the first entry in the log. Converting it to decimal, stripping of the last 6 digits gives us 1715536694 which when converted from epoch is 2024-05-12 05:58:14 UTC.

Analyzing Journal Files

We will predominantly use the in-built journalctl utility to extract information from the files. You can read up documentation on journalctl at https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man1/journalctl.1.html

Prelimnary checks

One of the useful options is to use the –header argument which shows high-level information about the concerned journal.

$ journalctl --file system.journal --header

File path: system.journal

File ID: 795d92d4b4744f10ade50183ce972cb0

Machine ID: b301f7a842a9475e9277df2feeb7dd35

Boot ID: 8d5452ac4c8a4f7cb8f43b5f2e7302b9

Sequential number ID: 9d2dc724f56d40e1964af2db2c812abf

State: OFFLINE

Compatible flags: TAIL_ENTRY_BOOT_ID

Incompatible flags: COMPRESSED-ZSTD KEYED-HASH COMPACT

Header size: 272

Arena size: 8388336

Data hash table size: 227086

Field hash table size: 333

Rotate suggested: no

Head sequential number: 11759 (2def)

Tail sequential number: 12176 (2f90)

Head realtime timestamp: Sat 2024-05-11 06:51:05 UTC (61828138c08b5)

Tail realtime timestamp: Sat 2024-05-11 07:07:04 UTC (618284cb34c0c)

Tail monotonic timestamp: 16min 31.526s (3b197ccc)

Objects: 2394

Entry objects: 329

Data objects: 1353

Data hash table fill: 0.6%

Field objects: 59

Field hash table fill: 17.7%

Tag objects: 0

Entry array objects: 651

Deepest field hash chain: 1

Deepest data hash chain: 0

Disk usage: 136.0M

Most importantly the above output indicates the timestamps of the first and last entry of this journal.

Now let us see some interesting things we can extract from the journals.

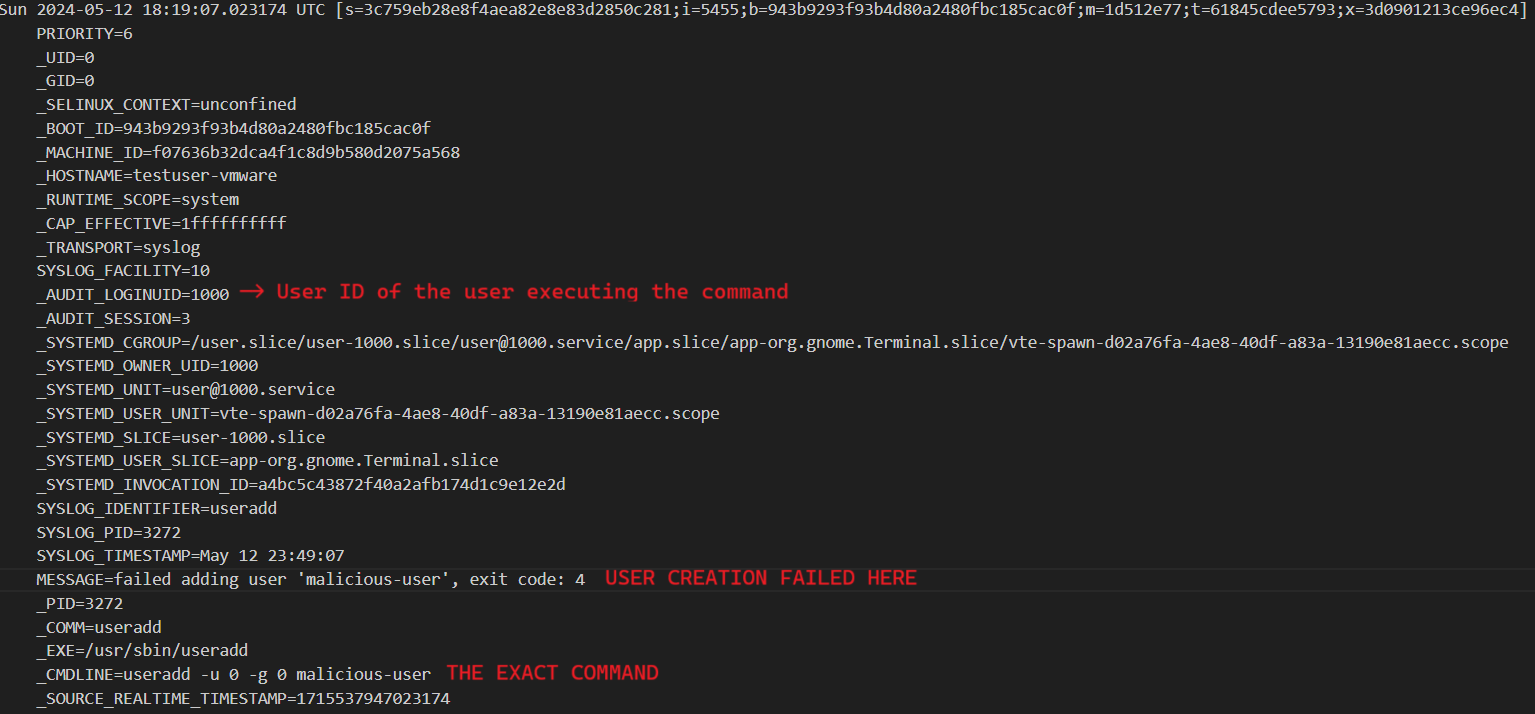

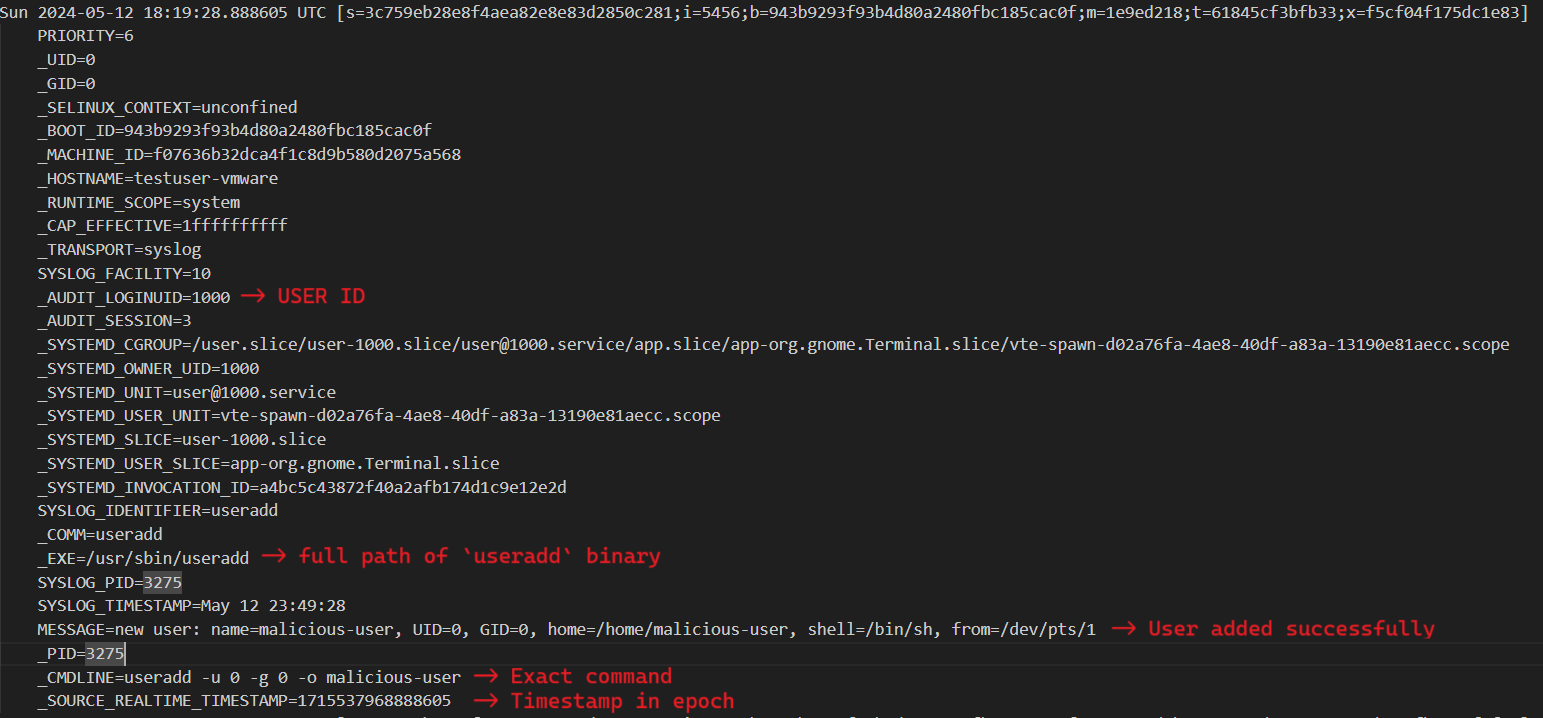

Finding suspicious user creation events

$ journalctl --file system.journal -o verbose > system-journal.txt

The output file would have a lot of events but in the screenshots I am just sharing the suspicious event itself. We see two very interesting events

Here we can see that user with UID 1000 tried to create a new user account named ‘malicious-user’ in the system. Right after this we have a successful creation event.

From the above images we get so much valuable info such as

- UID of the account executing the commands

- The exact command

- Status of the command i.e success/failure

- Timestamp in UTC

- Full path the binary

- Process ID of the binary

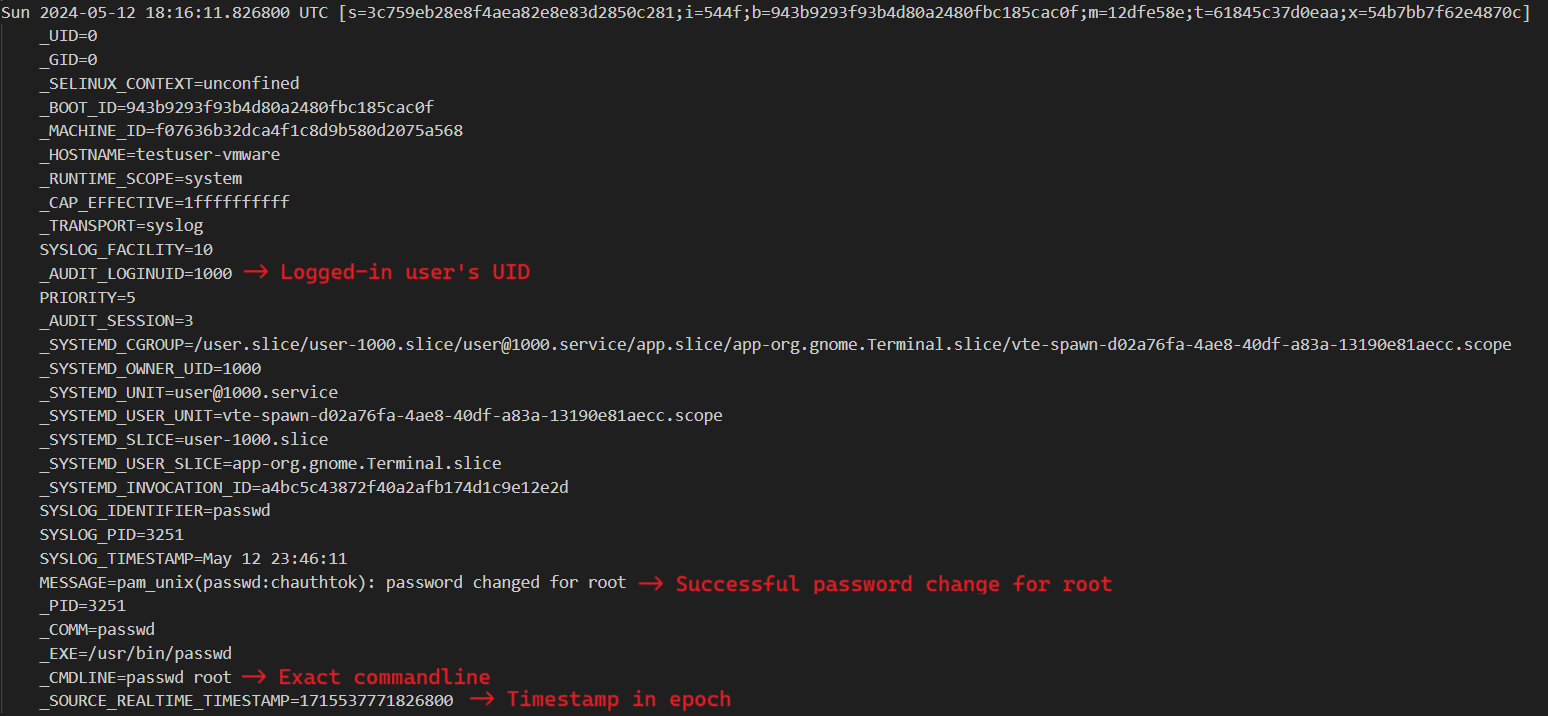

Finding password change events

In linux, password of a user is typically changed using passwd command. Let us see a few of these events within the journal. Here is the event of someone changing the password for the root user

Here we can clearly see that user (UID: 1000) executed the command passwd root and changed the password but this is not directly possible because to change root password, the command needs to be run under elevated privileges.

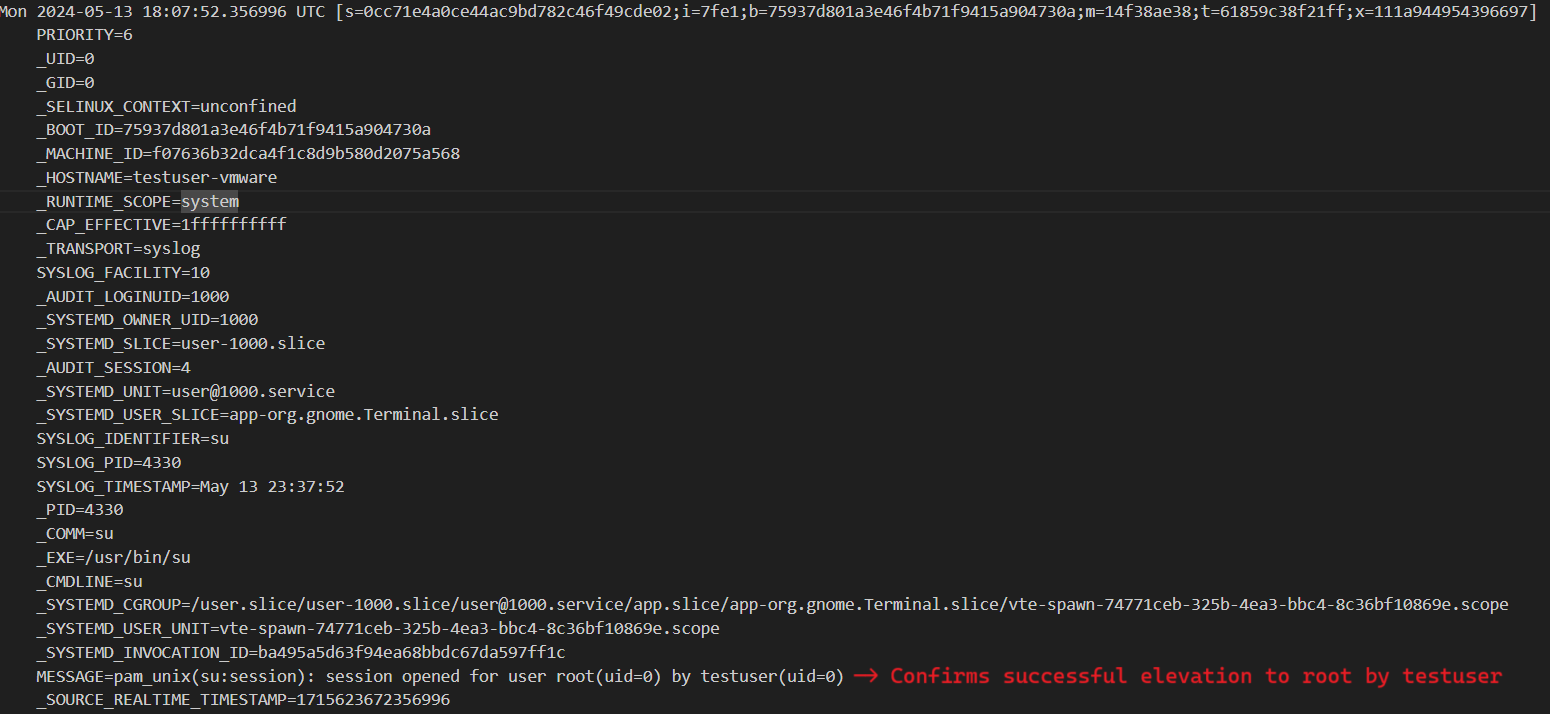

Finding user elevation events

Users regulary use sudo in Linux for various purposes. Let us see if we can find such events.

A user can elevate their session using sudo su.

Sample scenario

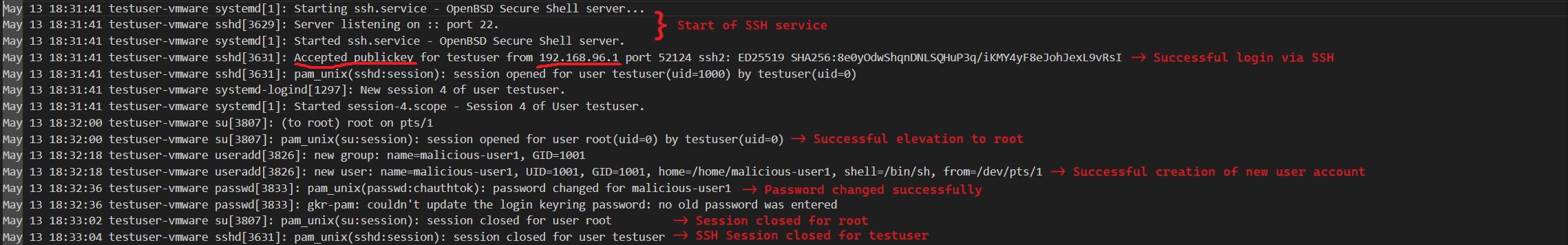

Let us consider a sample scenario where TA logs in via SSH to a user account, elevates session using sudo su, creates a new user, sets a password.

May 13 18:31:41 testuser-vmware systemd[1]: Starting ssh.service - OpenBSD Secure Shell server...

May 13 18:31:41 testuser-vmware sshd[3629]: Server listening on :: port 22.

May 13 18:31:41 testuser-vmware systemd[1]: Started ssh.service - OpenBSD Secure Shell server.

May 13 18:31:41 testuser-vmware sshd[3631]: Accepted publickey for testuser from 192.168.96.1 port 52124 ssh2: ED25519 SHA256:8e0yOdwShqnDNLSQHuP3q/iKMY4yF8eJohJexL9vRsI

May 13 18:31:41 testuser-vmware sshd[3631]: pam_unix(sshd:session): session opened for user testuser(uid=1000) by testuser(uid=0)

May 13 18:31:41 testuser-vmware systemd-logind[1297]: New session 4 of user testuser.

May 13 18:31:41 testuser-vmware systemd[1]: Started session-4.scope - Session 4 of User testuser.

May 13 18:32:00 testuser-vmware su[3807]: (to root) root on pts/1

May 13 18:32:00 testuser-vmware su[3807]: pam_unix(su:session): session opened for user root(uid=0) by testuser(uid=0)

May 13 18:32:18 testuser-vmware useradd[3826]: new group: name=malicious-user1, GID=1001

May 13 18:32:18 testuser-vmware useradd[3826]: new user: name=malicious-user1, UID=1001, GID=1001, home=/home/malicious-user1, shell=/bin/sh, from=/dev/pts/1

May 13 18:32:36 testuser-vmware passwd[3833]: pam_unix(passwd:chauthtok): password changed for malicious-user1

May 13 18:32:36 testuser-vmware passwd[3833]: gkr-pam: couldn't update the login keyring password: no old password was entered

May 13 18:33:02 testuser-vmware su[3807]: pam_unix(su:session): session closed for user root

May 13 18:33:04 testuser-vmware sshd[3631]: pam_unix(sshd:session): session closed for user testuser

Just this screenshot explains how valuable analysis of the journal is. If we were to drill down further using the verbose option, we would also get the commands associated with above activity as seen in above sections.

Conclusion

I hope this blogpost gives you some insight into analyzing journal files within Linux machines and how valuable they might be for us DFIR folks. There are still so many things within the journal. You can identify installation of linux packages, start/stop of different services etc…

This post is actually an extension of my original posts on X and LinkedIn. I thought writing a blogpost would be much more useful

- https://twitter.com/_abhiramkumar/status/1788869652229267653

- https://www.linkedin.com/posts/abhiramkumarp_dfir-linuxforensics-incidentresponse-activity-7194411180029796352-7sB4